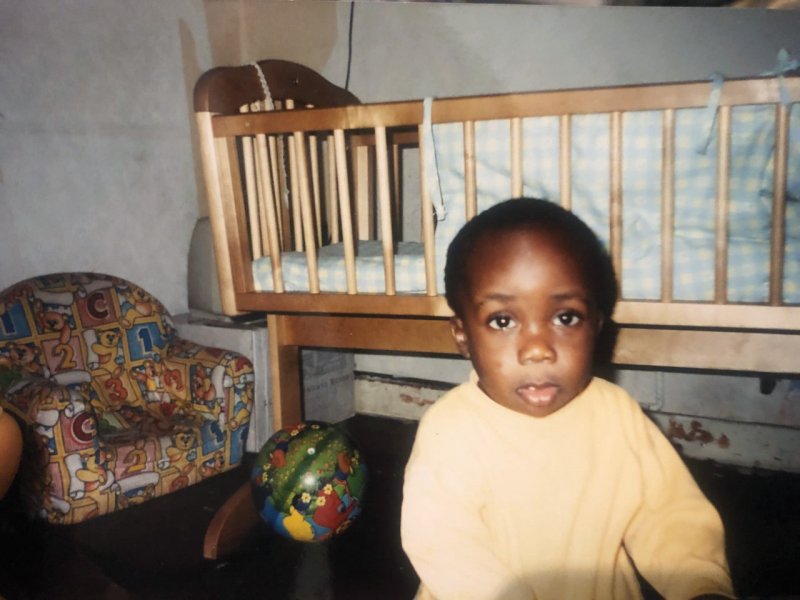

As a hyperactive child there were, according to my mother, two things that would calm me down: the family’s collection of Alphabets books – a series of 26 books from Albert’s Special Day to Ziggy and the Zig-Zag Race – and the prized yellow armchair I would read them in, patterned with teddies, numbers and letters.

The living room, where my chair was kept, is captured in this photograph – it is within our council flat in Battersea, south London, which we moved to in May 1998, 14 months after my birth, following a nightmare ordeal with homelessness and insecure housing. The cot kept my baby brother, Zachary, who was born five months after we moved in.

As I grew older, the location, the peeling wallpaper, the cracked walls, the drab colourlessness and the lack of furnishing in the household became a source of shame. I never had friends over, and when class assignments asked us to draw or write descriptions of our housing, I would lie. The late 1990s and the 2000s were not a time when one was made to feel proud of living in social housing, or within estates. It was a time when relying on local government accommodation was seen as a personal moral failure; it meant your parents must have declined the opportunity to “work hard” and live decently, instead raising their children among benefit scroungers, hooded youths, Asbo kids, chavs.

I carried this shame around with me for a long time – the idea that boys like me, who lived in quarters like mine, represented an outrage of national standards and were destined for unemployment, prison, or early death. It is not until recent years that I have been able to view photographs of the original rooms of this flat and feel pride, even joy.

The boy in this photograph knows nothing of shame. His imaginative mind takes in the colours of the toys, chairs and books all around him. The youngest children are often the best at grace and dignity, viewing their environments as a fun challenge for the imagination. The chair becomes a throne. The walls become canvases. I always wondered why my parents did not intervene when I drew on the walls: perhaps they concluded that our artwork was more about hope and creativity than naughtiness.

Last year, the Ikea Christmas advert addressed “home shame” and I was, initially, moved to see this feeling represented, particularly during the festive period. We never had Christmas trees, lights, tinsel. But the advert simply encouraged renovating with Ikea products – a possibility not so readily presented to many of us who experienced this phenomenon. Home shame for me was not overcome by the introduction of brushstroke vases, brass sculptures or oils on canvas. It was overcome when I began to look proudly on this photograph and see a happy child, who turned his grey home into his playground.

This article is from our “Photo that shaped me” series

This article appears in the 08 Dec 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Christmas special